Powerful Woman Aesthetics: Versace and Armani

In this fashion flashback, I’m reworking and extending from a visual essay I had previously written. Enjoy.

The end of the 20th century brought opposing aesthetics of the powerful woman to the fashion forefront thanks to Italian fashion giants Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace. As Anna Wintour famously referred to the Versace woman as the “sort of the mistress to Armani’s ‘wife’”, it is clear that Armani and Versace had differing perspectives on what it means to be a powerful woman in contemporary times. While both designers embrace the concept of emphasising the body, Armani adopts masculine aesthetics in contrast to Versace’s hyper-femininity. The 1980s saw a popular trend of power dressing where women were sporting Armani’s box-suits with broad shoulders as a means of affirming equal status to their male counterparts. Versace, although used similar aesthetics to Armani in his earlier work, transformed female power by embracing sensuality and ostentatiousness in the late 80s through to the 90s. Although both designers embrace glamour to heighten female status, Armani did so with an old hollywood appeal, intelligence and democracy while Versace played with excess, theatricality and sexuality.

While femininity and masculinity are critical terms that will be used throughout this visual essay, it is important to note these terms will be used in accordance with heteronormative values. However, questions on queer aesthetics in Armani and Versace’s body of work would make interesting analysis with more research and investigation. According to Horton, femininity refers to the “set of attributes (physical, psychological and emotional) that are associated with being a woman” that generally portray ideas of meekness and beauty (Horton, 2018). In contrast, hegemonic masculinity associates with “independence, competitivenes, muscularity and social and professional success” (Horton, 2018). Both terms are explored in Armani and Versace’s designs through the use of colour, material, cut and volume. Masculine aesthetics were emphasised with the 1980s power suit which, through padded shoulders and tapered hems, carries a common association with “masculine authority” and an aim to dress for success (Steele, 1997, 134). Armani was the pioneer of this phenomenon in a decade devoted to financial success and endless excess (Steele, 197, 130). While the power suit was a sartorial expression of the super body, a silhouette that promoted female muscularity and vitality, femininity, body-con and glamour were opposing aesthetics that portrayed a different style of female power. Glamour is “psychological quality that implies attraction, mystery and erotic allure” (Horton, 2018). In Versace’s early years, his designs combined both masculine and feminine aesthetics, however he completely embraced the eroticism and sensuality of glamour when he recognised the commercial potential of the highest-paid models of the 1980s and turned them into supermodels (Sinclair, 2015, 75). These models, including Cindy Crawford, Linda Evanglista, Christy Turlington and Naomi Campbell, defined their supermodel status while walking for Versace’s 1991 fall collection singing George Michael’s ‘Freedom! ‘90’. On account of Versace’s genius fusion with rock music and designer fashion, the supermodels exceeded fame beyond the fashion and modelling industry and became celebrities in their own right (Sinclair, 2015, 75).

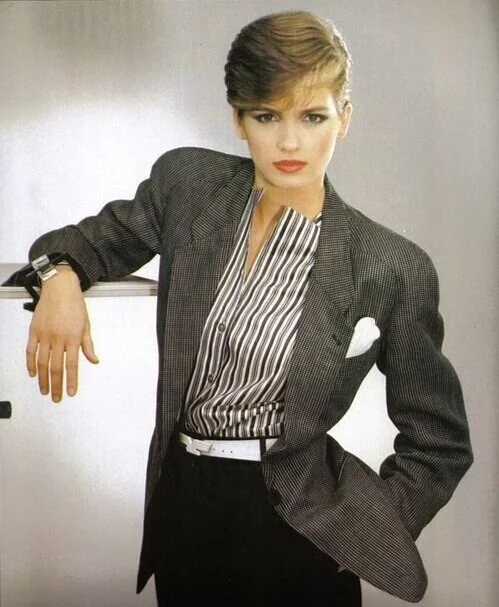

Armani and Versace utilise masculine characteristics in their designs to construct the powerful woman. In Armani’s Spring/Summer 1980 collection, model Gia Carangi wears an asymmetrical houndstooth suit with angular shoulder pads, a short boyish haircut and leather watch in a cool, relaxed pose with her elbow propped and hand in her pocket. The harsh angles of the shoulders exaggerates muscularity while the pose asserts dominance and authority. This masculine look is consolidated with the slim fit and high neck, concealing the female body and implying a conservativeness. Women had supposedly been liberated from such aesthetics of the power suit “because it seemed to distance them from the unwelcome stereotypical inferences of feminine powerlessness and subservience” (Steele, 1997, 134).

Versace’s sarong ensemble from his Spring/Summer 1989 collection includes box-shoulders and a conservative high neckline correspondent to Armani’s power suit. However, nearing the end of the power suit, Versace’s sarong ensemble dresses a woman “from the boardroom to the bedroom” in a “body-conscious, brazen style” with a short, tight-fitted sarong worn on the bottom (Sinclair, 2015, 12). Both designers used masculine aesthetics of the power suit as a device to dress the powerful woman, however Armani did so with explicit, exaggerated forms while Versace adorned them with hyper-femininity and vulgarity.

Gianni Versace Spring/Summer 1989

Scanned image from Gianni Versace, 1998 by R. Martin. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

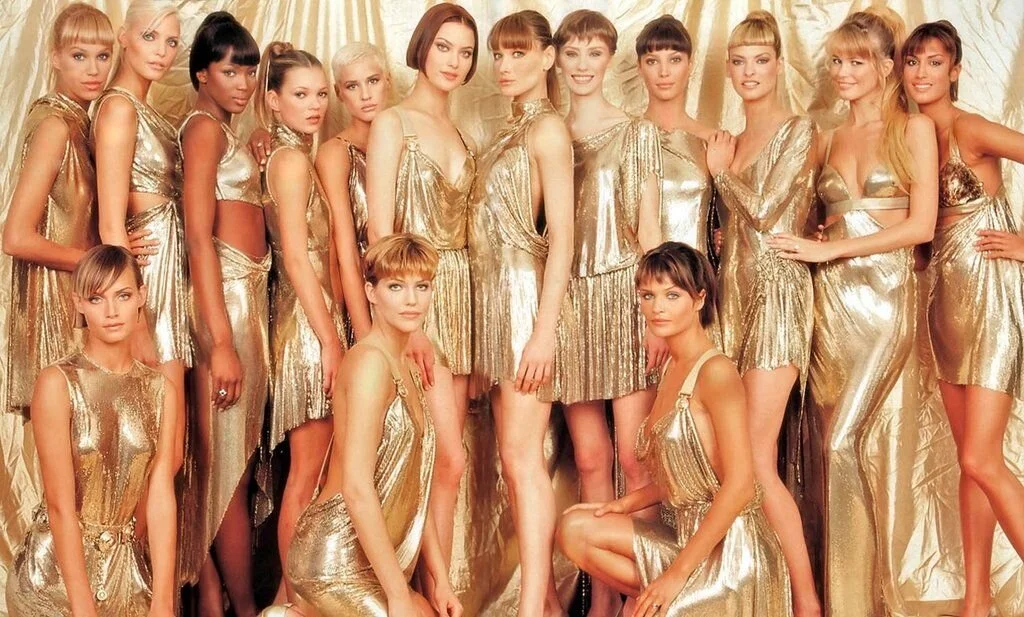

While masculinity was a significant design aesthetic used to create the powerful woman, neither designers neglected feminine aesthetics. Armani, although designed a masculine line of suits in his 1980 collection, did not want to create a “complete ‘man’s look’” for the modern woman (Armani, 1985, 207). The 1980 suit is complimented with bright glamorous makeup to bring a softness, where women can take “the menswear look and make it more feminine” (Armani, 1985, 207). While Armani’s application of femininity is done with “easy self-assurance and understated elegance”, Versace makes a forceful contrast with an honest sexuality and confidence in his sarong ensemble (Martin, 1997, 16). His see-through mesh material, decorated by a prolific use of beading and embellishment, reveals the breast while the tightly-wrapped sarong emphasises the curve of the hips. This creates an unflinching sensuality that celebrates excess, power and sexuality (Sinclair, 2015, 61). His gold metallic gowns of his 1994 collection oozes glamour and hyper-femininity as the seduction of his metal mesh highlights and eroticises the female body (Martin, 1998, 12). Versace’s attempt to be glamorous and vulgar in his designs portrays a sensual, confident woman who has the “powerful authority of a traditional menswear paradigm” (Martin 1997, 6).

Versace Fall/Winter 1994

Nadja Auerman, Cindy Crawford, Stephanie Seymour, Claudia Schiffer and Christy Turlington photographed by Richard Avedon, 1994. Courtesy of Thames and Hudson.

Armani and Versace both used supermodels to heighten femininity and glamour in their work. In his Spring/Summer 1980 campaign, Armani chose Gia Carangi to be the collection’s coat hanger. Carangi is arguably one of the pioneering supermodels who paved the way for the 90s icons that were to come (Cooper, 2018). She was the antithesis of other models of her time as she had no filter, wore no makeup and was a major personality (Cooper, 2018). Armani’s clever choice of model gives his designs a greater edge, where the already powerful woman makes the garments more powerful.

Versace also employed the legend of the supermodel at the start of the 1990s, however to a much greater extent. Like Gia, supermodels such as Naomi Campbell and Linda Evangelista were each individuals and their own character who had “bust and hips that go in and out, the way women are meant to” (Sinclair, 2015, 75). This is defined in Richard Avedon’s 1994 image for Versace’s Fall 1994 campaign. Here, we see Nadja Auerman, Cindy Crawford, Stephanie Seymour, Claudia Schiffer and Christy Turlington posed statuesque atop a foundation of naked muscular men. Gold metal mesh gowns cling to the body, with cuts that reveal the side torso, leg, bust and décolletage that not only emphasises the body’s presence but the body’s titillation (Martin, 1997, 15). This god-like drapery portrays the models as a group of untouched goddesses, a recurring concept that would be associated with these women in the real world. Contrast to Armani, Versace was known for enhancing their natural beauty by “revealing their perfect bodies and bringing out their charisma” as well as assembling them “into a team who took people’s breaths away” (Stanfill, 2014, 283). Both Armani and Versace demonstrate aesthetics of the female super body by employing supermodels as their ambassador, where Armani dresses Gia as a powerful business woman and Versace dresses his supermodels as eroticised goddesses.

Backstage at Versace Fall/Winter 1994 show.

The last quarter of the twentieth century saw an emergence of post-modernist references in fashion design, particularly evident in the Italian designers’ work. Armani’s asymmetrical lapel is a deconstruction of traditional masculine rectitude shown in his tailoring, symbolising a shift in gender power dynamics (132). Equally important is the way his power suit appropriates old Hollywod glamour, breaking the cliché of cross-dressing initiated by Marlene Dietrich in the 1930s (Stanfill, 2014, 232). Versace also intertwined the past with contemporary themes in his designs (Spindler, 1997). In his 1994 collection, the classical wet drapery of the gold mesh is reminiscent of Roman history, where women “seize real power from men” (Martin, 1997, 5). This is clearly evident in Avedon’s 1994 image where he takes Versace’s historic reference and delivers it in an erotic, bodily representation of female empowerment. Connecting this appropriated classical design aesthetic and imagery with the contemporary supermodel presents a hyperbolic and reimagined history that transcends into current times.

Overall, the aesthetics of a powerful woman changed dramatically between the 1980s and 1990s, from adopting masculinity to fully embracing the power of femininity. Both Giorgio Armani and Gianni Versace used masculine design aesthetics of the power suit as a device to empower the career woman of the 1980s. Where Armani designed the power suit with understated elegance, Versace combined it with sensuality. The Italian designers could not have neglected femininity in their designs, however Armani treated femininity with demure and traditional beauty where Versace’s bold and foreful embrace of sexuality and vitality shamelessly empowered the woman as she was. This relates to both designers’ recognition of the supermodel. Both used models whose fame transcended beyond the fashion industry, however Versace brought a “look but can’t touch'“ appeal to the supermodels of the 1990s where Armani dressed Gia as a relatable figure to the female consumer. Post-modernism played a significant role in defining the contemporary for both designers as they both drew inspiration from historic female figures and reimagined them to suit the present. Thanks to Armani and Versace, the powerful woman represents self-confidence, sophistication, intelligence and sensuality.

Bibliography

Armani, G. (1985). “Womenswear from the King of Menswear”. In G. Mirabella (Ed.) Vogue (p. 207). New York: Conde Nast Archive.

Cooper, S. (2018). The Story of Gia – the world’s first supermodel who died of Aids at 26. Retrieved 13 October 2018, from www.dazeddigital.com/fashion/article/41317/1/the-story-of-gia-the-world-s-first-supermodel-who-died-of-aids-at-26

Gundle, S. (2008). “Style, Pastiche and Excess”. In Glamour: A History (p. 344). New York: Oxford University Press.

Horton, K. (2018). DFB402 – Glossary of Key Terms. Retrieved 27 September 2018, https://blackboard.qut.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-7483727-dt-content-rid-16782785_1/courses/DFB402_18se2/DFB402_Glossary%20of%20Key%20Terms%20%282%29.pdf

Lehnert, G. (2010). “Gender”. In L. Skov (Ed.), Berg Encyclopedia of World Dress and Fashion: West Europe (pp. 452–461). Oxford: Berg. Retrieved October 23 2018, from http://dx.doi.org.ezp01.library.qut.edu.au/10.2752/BEWDF/EDch8075

Martin, R. (1997). Versace (1st Edition). London: Thames and Hudson.

Martin, R. (1998). “Introduction”. In J. P. O’Neill (Ed), Gianni Versace (pp. 11-15). New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

National Gallery of Victoria. (n.d.). Super Bodies – Heroic Fashion from the 1980s. retrieved 13 October 2018, from https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/exhibition/super-bodies/

Sinclair, C. (2015). Vogue On: Gianni Versace (1st Edition). London: Quadrille Publishing Limited.

Spindler, A. (1997, July 16). Gianni Versace, 50, the Designer Who Infused Fashion With Life and Art. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1997/07/16/style/gianni-versace-50-the-designer-who-infused-fashion-with-life-and-art.html

Stanfill, S. (2014). Italian Glamour - The Essence of Italian Fashion: From the Postwar Years to the Present Day (1st Edition). Milan: Skira.